From rural roots to modern medicine: College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

A CSU @150 Story by Jessica Cox published Nov. 21, 2019When the Morrill Act establishing land-grant colleges became the law of the land in 1862, teaching the “agricultural arts” included instruction in the professional care and feeding of farm animals.

The primary focus of veterinarians was the health of livestock raised for meat and dairy products, as well as the horses and mules that provided the nation’s primary mode of transportation.

Ready to meet the needs of farmers and ranchers, the Colorado Agricultural College included veterinary science among its first courses launched in 1879, the same year classes began at the new land-grant college.

After some early leadership challenges, the three-year Doctor of Veterinary Science program became official in 1907. George Glover, one of CAC’s first graduates and first head of the new Department of Veterinary Science, was optimistic about the program’s future, which was also expanding its focus to include care for the dogs and cats that Americans were increasingly bringing into their homes as pets.

“We now have a clinic, in number and variety of cases equal to any veterinary college in the land,” Glover said in 1909. “We have treated over a thousand cases a year.”

In 2018, the James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Colorado State University treated 47,000 cases.

From helping ranchers and farmers maintain food safety to providing compassionate care for animals large and small, veterinary medicine at Colorado State University continues to represent the land-grant values of service, education and research while still meeting the needs of a changing world.

The Division of Veterinary Medicine, officially established in 1933, became a college within what was then known as Colorado A&M in the 1940s. The first veterinary hospital on campus, named for Glover, opened in 1949. In 1967, the “vet college” added “Biomedical Sciences” to its name, recognizing the stature of the many Ph.D. researchers within the program. Faculty continue to explore health challenges for humans and animals, with world-renowned research in infectious disease, orthopedics, neuroscience, cancer biology, animal reproduction, and translational medicine.

CSU @ 150 stories

Read more stories about the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

CAC grads helped shape nation’s veterinary education

All creatures great and small cared for by CSU’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital

Out of the gate: New horse hospital breaks ground at CSU Veterinary Health Complex

Enduring mission, novel approach

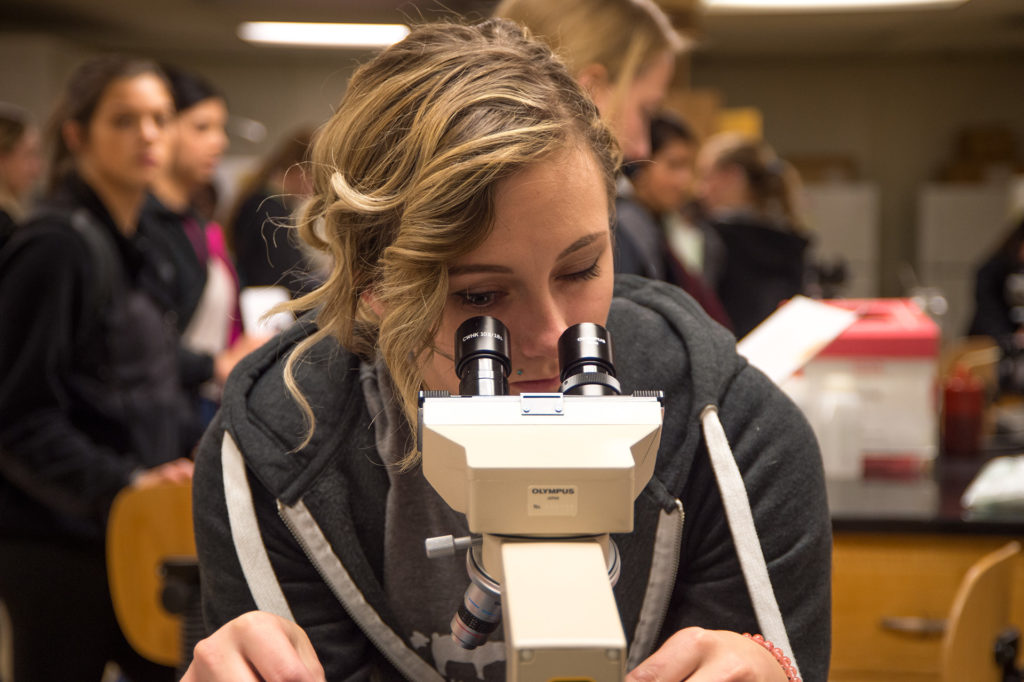

While the college’s mission and land-grant heritage haven’t changed over its 150-year history, the tools used to fulfill that mission have evolved.

“Who would have imagined we could travel through the human body using virtual reality, or that we would have a multi-million-dollar Translational Medicine Institute that’s discovering new therapies for animals and people?” said Dr. Mark Stetter, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “Our core mission hasn’t changed, but technology has changed dramatically.”

One challenge faced by Glover and other early veterinarians at CAC was establishing a dedicated course of study and research in veterinary medicine, distinct from livestock management. But the two fields remained inextricably linked.

Ruth J. Wattles, in The Mile High College, her unpublished history of Colorado A&M on its 75th anniversary in 1949, noted: “Much of the work of the Veterinary Section … has been pure science, a contribution to the world’s knowledge. On the other hand, the veterinarians have not been cloistered in … the laboratories. They have been in touch with men on the ranch and the range…. When these men saw their livestock, the source of part of their livelihood, dying, they asked the help of the veterinarians, and the scientists gave the results of their training in research to the livestock men.”

Some of this early research concentrated on eliminating tuberculosis in Colorado herds; identifying poisonous plants on the range; the effects of high altitude on cattle; and addressing feed diseases in sheep and poultry.

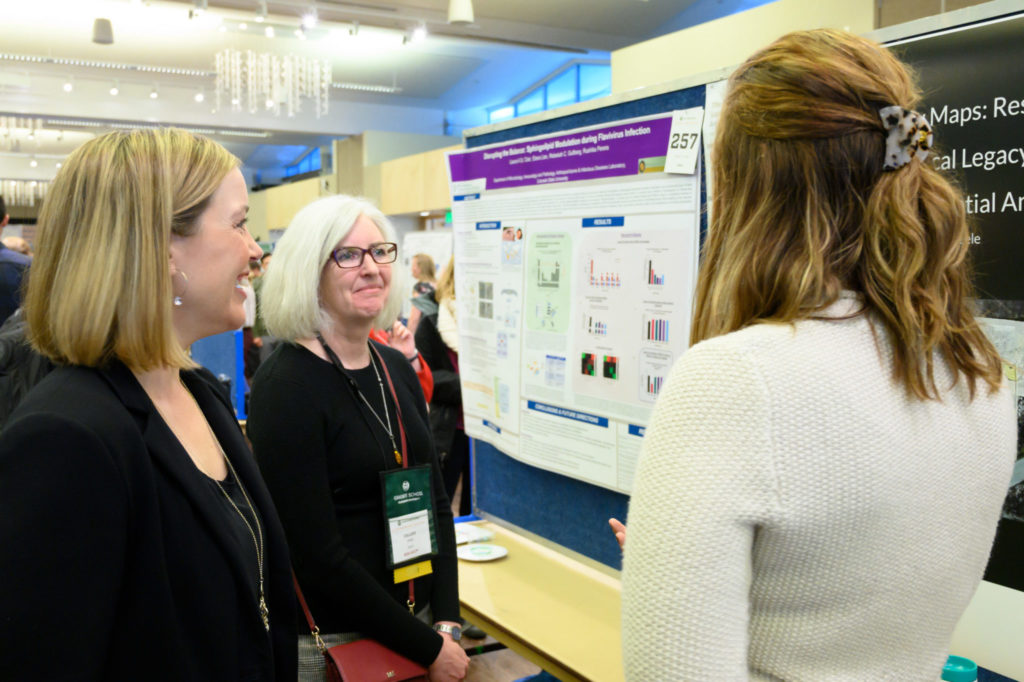

Those researchers collaborated with botanists and entomologists on campus to attack pressing problems, and efforts across campus today embody this collaborative approach to human and animal health, when like-minded scientists work together to solve urgent problems. A prime example is the annual CVMBS Research Day, when students of all levels and from various programs come together to present and learn about health.

“Research Day is not just a ‘veterinarian day’ or a ‘Ph.D. day’ – it’s an opportunity for people in animal health, human health, and ecosystem health to realize we can improve how we deliver on our mission by working together,” said Stetter.

Events like Research Day and programs like the Center for Healthy Aging and the One Health Institute continue the land-grant mission into the 21st century, while some new efforts harken back to the college’s agricultural roots.

Returning to rural roots

In the 21st century, a growing need for veterinarians in rural areas has prompted efforts to enhance livestock and food animal veterinary medicine education, bringing the program full circle to its land-grant origins.

A collaborative program with the University of Alaska Fairbanks graduated its first class of D.V.M. students, equipped with knowledge about public health, rural medicine, and food security issues, in May. Colorado’s Veterinary Education Loan Repayment Program helps address the shortage of veterinary medicine expertise in rural areas, too, providing veterinarians who work in remote communities financial assistance with their student loans.

In human health, the college is also creating new educational opportunities for Colorado medical students. In partnership with the University of Colorado School of Medicine, CSU will enroll the first students in its medical program in 2021. Students will earn medical degrees from the CU School of Medicine and benefit from the expertise of faculty from both universities.

Reflecting an industry need for health and medical professionals, the college’s biomedical sciences undergraduate program will be restructured for Fall 2020. Incoming students will be able to choose one of three concentrations within the biomedical sciences major: anatomy and physiology, environmental public health, and microbiology and infectious disease. All concentrations provide the prerequisites necessary for applying to graduate school and professional programs, like medical, veterinary, or pharmacy school.

What started with improving health for primarily cows and horses has developed into improving health for humans, cats and dogs, lizards, ferrets, birds, rabbits, snakes, and other animals, companion or otherwise (and still plenty of cows and horses).

Access for all

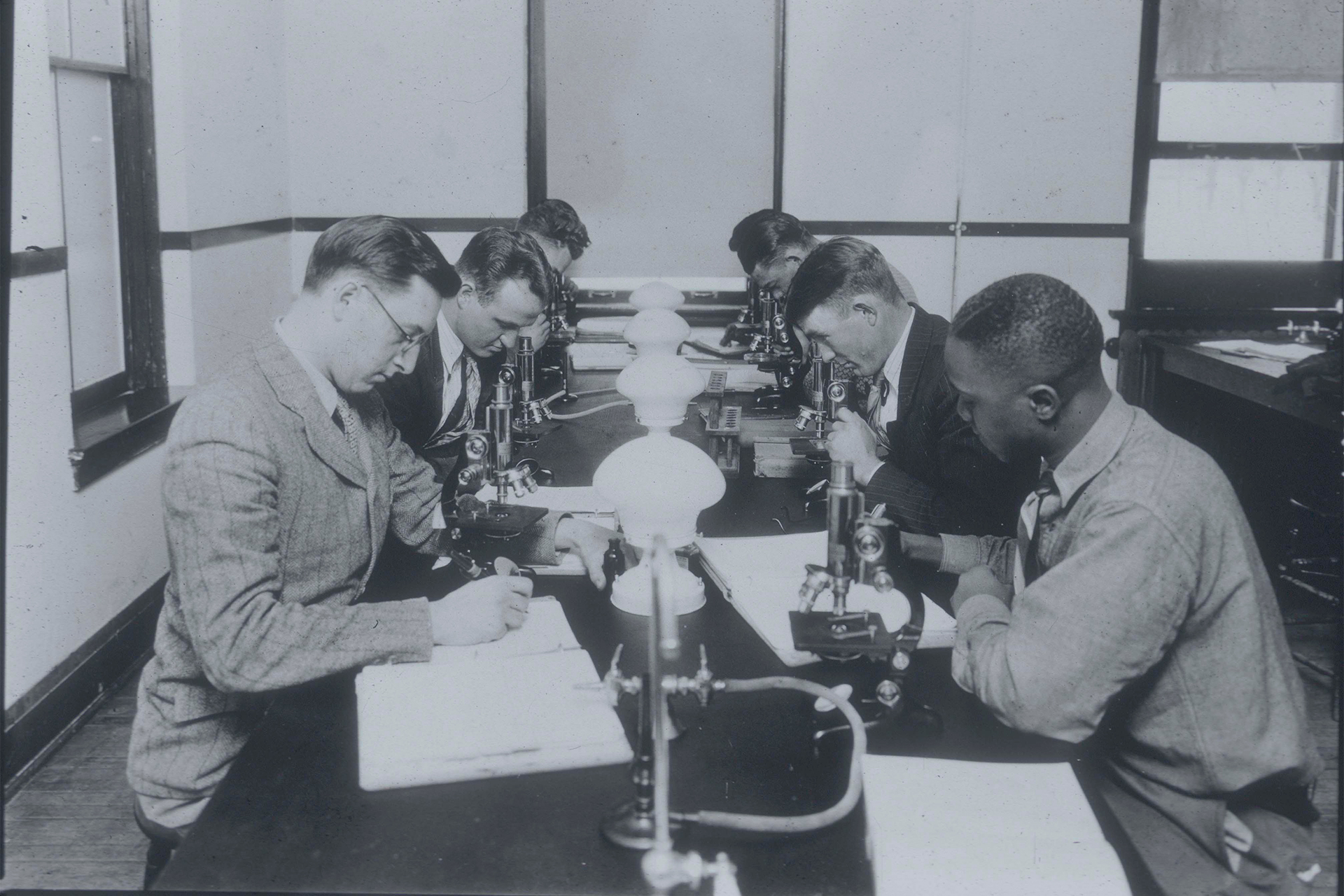

Historically, the veterinary profession – and education – has been dominated by men. Libbie Coy, the first female graduate of Colorado Agricultural College, was required to take a class in French while her two male classmates, including George Glover, took courses in veterinary science and stock-breeding.

A century later, in 1983, college historians commented that “the future of veterinary medicine must include the expanding role of women in the profession.”

In 1947, Mary Dunlap, founder of the Association for Women Veterinarians, was certain about the future of women in veterinary medicine: “It is the duty of a pioneer to blaze a trail, to set up markers for the guidance of those who come after. I have no doubt that the controversial question of whether women should be admitted to the veterinary college will be in the end settled.”

The program graduated its first female veterinarian, Evelyn Hermann Keagy, in 1932 and nowadays the matter seems not so controversial, as 84% of the 2019 class of first-year veterinary students are women. The college has come a long way to bridge the gender gap – in fact, Associate Dean for Research Sue VandeWoude was elected into the National Academy of Sciences this year – and strives for diversity in other ways too.

“Science is so collaborative now. Veterinary medicine used to be a male-dominated profession, but that’s changing,” said Stetter. “A major priority is to recruit faculty, staff, and students from underrepresented populations into our programs and the various health professions.”

In an effort to be a welcoming and supportive place for all faculty, staff, and students, the college’s Diversity and Inclusion committee supports student organizations, faculty and staff workshops, recruitment and retention efforts, and grant-writing and research assistance to contribute to the college’s goal of inclusive excellence.