When Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Paul Heyliger suggested to Associate Professor Hussam Mahmoud the idea of conducting blast research at Colorado State University, Mahmoud didn’t believe it could be done.

“I said, ‘It’ll never happen. There will be so many obstacles, it’s just not possible,’” Mahmoud recalled.

While there were many obstacles, including strict and extensive Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives regulations, cooperation across CSU units made it possible for the professors and two graduate students to conduct research that could help save lives. Their findings are published in three papers in Engineering Structures, and a fourth paper is under review.

“In my opinion, our collaboration has been a model of what a university should be like. We have been able to maximize existing resources in the hope of educating students and further understanding in this unusual area,” Heyliger said in an email thanking Environmental Health Services Director James Graham for his department’s help in the effort.

Colorado State University is one of only a handful of academic institutions in the U.S. authorized to conduct explosives research. Three of these are in Colorado, and CSU has the most extensive program among them.

If you weren’t aware CSU has an explosives program, there’s a good reason for that.

“Part of our Homeland Security plan is to be very low key,” said Karl Swenson, CSU’s explosive safety officer with Environmental Health Services. “Our test ranges and explosive storage bunker locations need to be kept confidential.”

Swenson and Chris Giglio, chemical management officer with Environmental Health Services, are licensed to handle and store explosives, and they enabled the testing proposed by the civil engineering professors and grad students.

Inspired by tragedy

Assal Hussein, a Ph.D. student from Iraq, wanted to save lives in his home country by investigating how to mitigate blast impact from terrorist attacks. His brother was killed in an attack in Iraq while Hussein studied at CSU.

Terrorists had been targeting civilians in open areas to maximize casualties. Hussein, Heyliger and Mahmoud wanted to show that low-cost, easily constructed blast barriers in regions of high risk could reduce injury and loss of life.

“We are less interested in high-tech systems that are either very expensive and/or very difficult to install and more interested in a low-tech system that could be installed by two teenagers in a pickup truck,” Heyliger said.

They found that even the simplest plywood wall could help mitigate blast loading, the pressure imposed by an explosion, by lowering the pressure field produced by the blast. Prior studies had demonstrated the effectiveness of concrete or steel structures for mitigating blasts, but this was the first time light-weight, cost-effective wood had proven to be useful as a blast barrier. Wood is easy to obtain and use, even in the arid Middle East.

Next, the team added another readily available material: sand. They constructed a box out of wood and filled it with sand. As expected, the wood-sand-wood wall structure performed better, partly due to its increased mass. The sand dissipated the energy from the blast wave, and – importantly – the wall didn’t shatter and create flying debris. Most explosion injuries and deaths are from projectiles and not the shock wave itself.

From structures to biomechanics

Because it is so difficult to get approval for explosive testing, there was a dearth of data on the threshold where blast wave pressure starts to cause bodily harm. M.S. student Amanda McCann, who is also a member of the National Guard, wanted to fill this gap in knowledge and find the distance at which a person is safe from an explosion’s pressure wave.

“My experience in the military and knowing soldiers who have suffered the effects of explosives increased my interest in the subject and inspired me to know more about it,” McCann said. “The more we know about the cause of a problem, the more we can do to protect people and find ways to reduce the danger associated with explosive shock waves.”

Kirk McGilvray, assistant professor in the School of Biomedical Engineering and Department of Mechanical Engineering, provided the team with leftover animal tissues for their studies. To ascertain blast damage on biological tissue, McCann focused on eardrums, which are highly susceptible to tears and ruptures from explosive events.

The team was able to determine the threshold of blast wave pressure for eardrum damage and refine the levels of pressure that are likely to cause harm. They also proved their simple blast walls reduced damage to biological tissue.

Biggest bang for no bucks

These discoveries would not have been possible without the work of many across campus and the city, including the Fort Collins Police Department, which donated materials for some of the tests. The projects were unfunded and relied on volunteered time and materials.

“There have been a lot of people helping us and we are extremely grateful for that assistance,” Heyliger said.

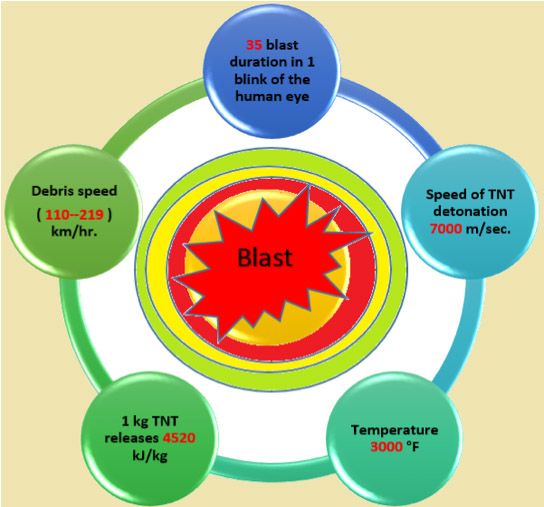

The team tested relatively small charges, up to .75 kilograms of TNT, compared to the 5-10 kilograms that might be carried in a suicide vest. Though not massive, the charges allowed the researchers to validate their numerical models, so they can simulate larger explosions.

Mahmoud said working on these projects has been exciting because they have a direct outcome that benefits all humanity.

“Being originally from the Middle East, I understand the importance of this type of work for civilians there. And in the U.S., as an American, this is important for us as well. We’ve suffered from that stuff before,” Mahmoud said. “If we can continue to develop new ways and strategies to protect the public, whether it’s here or abroad, it’s the best outcome of any research.”

Hussein is now a faculty member at the University of Diyala in Iraq. McCann recently returned to Colorado from National Guard training. She is employed by structural engineering firm Raker Rhodes in Fort Collins.