What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Colorado, where five talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people representing a diversity of experiences and backgrounds in gender identity, physical ability, whether they are Indigenous, native born, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an "American.”

Ivy Winfrey reports for Next Generation Radio with Colorado Public Radio Filmmaker Usama Alshaibi came to the United States from Iraq as a child. To him, being American means being proud of who you are and where you came from in the face of overwhelming resistance.

Illustration by Emily Whang

To one Arab-American filmmaker, being American is having the possibility of change

Usama Alshaibi has always been attracted to the idea of aliens.

“I think that’s how it feels when you come from somewhere else,” Alshaibi said. “I mean, they also call us alien residents.”

Alshaibi is a filmmaker and instructor at Colorado State University. He currently lives in Boulder, Colo. with his 10-year-old daughter.

Alshaibi was born in Baghdad, Iraq in 1969.

When he was four years old, Saddam Hussein’s government had a program that would grant scholarships for students, like Alshaibi’s father, to study in the west, which brought Alshaibi and his family to Iowa City, Iowa.

'I’m probably more American than most people'

“We would travel back and forth between Iraq and the United States to visit,” Alshaibi said. “So I was aware that I was from Iraq and I had this feeling like, ‘oh, I’m a foreigner, I’m from another place.’”

During this time, he learned to connect to the world through art and painting, and developed a knack for it.

When his father’s study ended, his family moved back to Iraq.

But when the Iraq-Iran War broke out in the 1980s, his family was forced to flee to Jordan, then Saudi Arabia, and eventually ended up back in the United States.

As Alshaibi grew up, he kept returning to art, he discovered he had a talent for Super 8 film production, and decided to go to film school in Chicago.

Then, during the second U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2004, Alshaibi had a calling.

“I called my dad and I said, ‘Do you want to go back to Iraq?’” Alshaibi recalls.

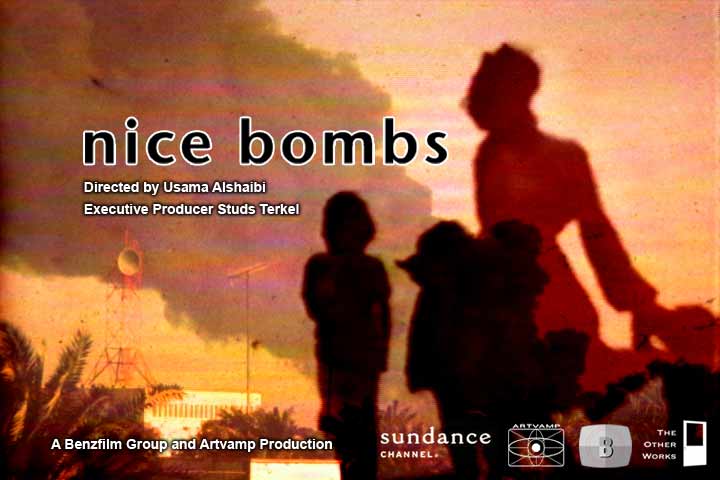

He documented his return to Baghdad in his first feature-length documentary, Nice Bombs, named after a moment in the film when, upon hearing a nearby explosion, his cousin Tareef explained, “It’s a bomb, a nice bomb.”

“I was really disgusted with how the media was portraying Iraq, there was no objective media,” Alshaibi said. “They were all embedded with the American military. So the perspective was through a tank, through a gun. And a lot of my work is me responding to that frustration and that anger.”

When he went back to Iraq, Alshaibi had this fantasy that things would go so well that he could move back, but he quickly realized how American he had become, and how different that was.

A photograph of Usama Alshaibi and his younger sister as children sits on his bookshelf at his home in Boulder. Photo by Ivy Winfrey.

Usama Alshaibi’s first feature-length documentary released in 2006, detailing his return to Baghdad nine months after the U.S. Invasion of Iraq. Photo Courtesy of Usama Alshaibi.

Usama Alshaibi sits at his home work station. He works as an instructor at Colorado State University and makes many fiction and nonfiction independent films. He produced five short films in 2020, including The Shadow, a response film to the 2014 film American Sniper. Photo by Ivy Winfrey.

Usama Alshaibi stands in his backyard in Boulder, Colo. holding an Iraqi flag. When he first came to the United States as a child, he didn’t speak any English and that led him to discover his love for art, he said. Photo by Ivy Winfrey.

Alshaibi had always had this vision of what America was. He said that vision of America was “you know, the Brady Bunch and all the TV shows that I watched in the seventies. It’s just white blonde kids.”

But that changed when he moved to Chicago.

“I remember I was in a neighborhood and there were like five different languages being spoken around me and everyone was from somewhere else,” He said. “Being from Iraq, an immigrant, whatever the hell my story was, was normal, boring, benign … I could walk into a neighborhood and feel like I’m in another world.”

Alshaibi became a citizen of the United States in 2002. To him, the spirit of being American is to have room to be yourself, and fight for that right.

To be American is to have the freedom to define for yourself what it means to be American.

“The reason earlier immigrants came here, our mothers and fathers and families wanted a better life,” Alshaibi said. “They could have gone to other countries, but what was it about here? And I think it was the possibility of change.”

Usama Alshaibi lives in Boulder, Colo. with his 10-year-old daughter Muneera. “In many ways, our children inherit not only our stories, but our traumas,” he said. “And so I have to balance that out by saying ‘this is who you are, this is where you’re from’ and to counter the challenges that come with that … and make sure she’s strong and confident.” Photo by Ivy Winfrey.